Image courtesy of the Schmidt Ocean Institute

A 20 Year Deep-Sea Legacy

Challenger 150 is a continuation of two decades of deep-sea effort that has involved scientists, economists and lawyers around the world under the umbrella of two major initiatives: INDEEP (International network for scientific investigation of deep-sea ecosystems) and DOSI (Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative), which are legacies of the deep-sea projects of the Census of Marine Life programme (2000-2010).

In 2021, the International Oceanographic Commission formally endorsed Challenger 150 as a new 10 year programme of deep-sea science under the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development.

A history of deep-sea research and stewardship

-

2000

Start of the Census of Marine Life programme, a 10-year international effort undertaken to assess the diversity, distribution, and abundance of marine life

-

2010

Completion of Census of Marine Life which had stimulated the discipline of marine science, engaging some 2,700 scientists from around the globe. The scientific results were reported on October 4, 2010 at the Royal Institution in London.

-

2011

International network for scientific investigation of deep-sea ecosystems (INDEEP) established, a global collaborative scientific network dedicated to the acquisition of data, synthesis of knowledge, and communication of findings on the biology and ecology of our global deep ocean, in order to inform its management and ensure its long-term health.

-

2013

Deep-Ocean Stewardship Initiative established, a global network of experts seeking to integrate science, technology, policy, law and economics to advise on ecosystem-based management of resource use in the deep ocean and strategies to maintain the integrity of deep-ocean ecosystems within and beyond national jurisdiction

-

2015

Initial discussion about a new global deep sea programme at Challenger Deep Sea Special Interest Group meeting

-

2017

DOSI Decade of Deep-Ocean Science working group continues the work of INDEEP

-

2018

Royal Society meeting (London), to discuss “Beyond Challenger: a new age of deep-sea science and exploration”

-

2019

SCOR working group 159 established

-

2020

Challenger 150 formed from efforts of DOSI Decade WG, SCOR WG 159 and Challenger Deep Sea Special Interest Group

-

2021

Challenger 150 is endorsed by IOC-UNESCO as a action of the UN Ocean Decade

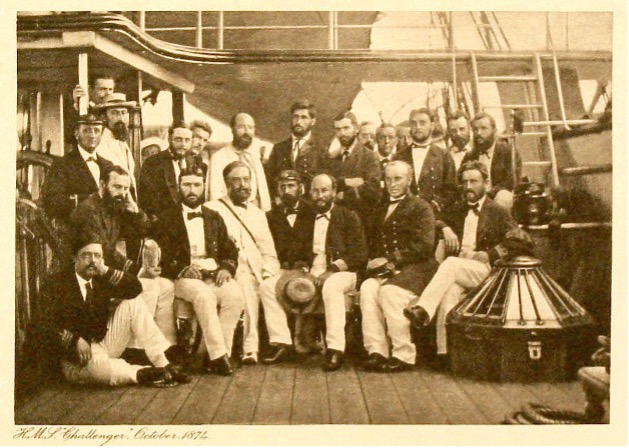

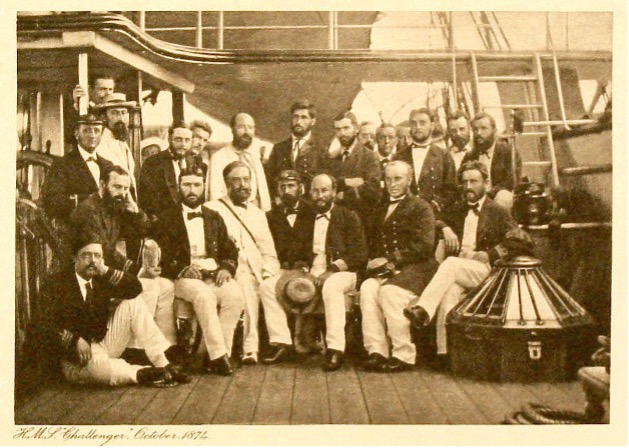

The name “Challenger” is associated with exploration of new frontiers. One hundred and fifty years ago ‘HMS Challenger’ spent four years circumnavigating the globe, mapping the seafloor, recording the global ocean temperature, and providing us with a first global view of life in the deep sea. It is considered the birth of deep-sea biology and oceanography. The name was later used by the NASA space programme, first as the name for the Apollo 17 Lunar Module that landed on the Moon in 1972, and later as the name of the space shuttle Challenger that flew the first American woman, African-American, Dutchman and Canadian into space. Today the name persists as the deepest point of the ocean, the bottom of the Mariana Trench where, in January 1960 Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh made the first human descent to the Challenger Deep in the bathyscaphe Trieste. More recently, in March 2012 film director James Cameron made the first solo descent in the deep-submergence vehicle Deepsea Challenger. We use the name Challenger here to invoke the same spirit of exploration embodied by the previous Challengers, and to recognize the importance of that first global deep-sea biological dataset that, for some parts of the ocean, remain the only data available.

However, we fully acknowledge that past exploration has involved colonialism and exclusion. The first Challenger was all white, all male, and took place in a time of imperialism and repression perpetrated largely by western European nations.

Deep-sea biology has thankfully moved on in the last 150 years, but the rate of change has been painfully slow.

In the majority of countries undertaking marine research, women were largely excluded from sea-going expeditions until the mid 20th century. In sea-going sciences like deep-sea biology, there remains underrepresentation of groups who identify as Black, Asian or as a member of another (non-white) ethnic group, women, and individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, or as having other gender/ sexual identities (collectively referred to as LGBTQIA+), those from low-income backgrounds, and those who have a form of disability (Hendry et al., 2020). This must change.

One of the key aims of Challenger 150 is to forge a new face for an historic name, which in keeping with the Ocean Decade, is inclusive, representative and equitable.